I remember getting my first pap smear when I was sixteen. I didn’t take my bra off, which confused the doctor who just shook his head quickly at the nurse and said not to worry about it. I was so obviously mortified by nudity that he stopped trying to make conversation about halfway through and just got in and out as quickly as possible.

Those were the days. Sometimes I miss my dignity and self-respect. After a couple of decades filled with multiple surgeries and childbirths, I don’t really remember what modesty feels like anymore. I suppose every woman gets that way as she ages; dropping her panties and spreading them for public viewing just becomes an old habit. Right now, though, I am feeling pretty lucky that regularly occurring indignities no longer phase me.

Narcotics are amazing. If you have pain- I mean real pain, the kind that won’t let you focus on anything else- narcotics can be your savior. At 23, fresh out of the hospital with a bandaged splint on my right leg and a skin graft site covering my left cheek, I was grateful for the existence of narcotics as well as my mother’s insistence that I take them on schedule to avoid the pain all together. Wise advice from a seasoned RN. She failed to mention that narcotics have a miserable side effect though: Constipation. I can’t recall how many days went by before I finally told her in tears that I couldn’t go to the bathroom to save my life and things were starting to get dire. You would think by this point I’d have had no secrets left from her. This is the same caretaker who had catheterized me herself in the hospital and was at this point blow-drying my naked rear end twice a day to speed the graft site healing. Still, I waited to enlist her help until I couldn’t wait any longer.

My mother is a saint. She patiently explained to me that this was very common with narcotics and gave me some stool softeners and calmed me down. When this failed to do the trick and instead exacerbated an already somewhat urgent situation, she ran to the store to buy a Fleet enema.

If you’ve never had an enema before…screw you. I don’t how your karma is so great to have avoided this major life milestone, but I’m certain it will catch up with you. I’m off-topic. An enema is either water-based or oil-based and is essentially just a big squirt bottle full of liquid to be injected directly into your rectum. Once it is in there, it breaks up whatever stool is causing a blockage and lubricates the pathway to enable you to poop. It’s not rocket science, but it’s effective. In order for this to work, however, you have to squeeze your anus closed and not let anything out until it has been in there long enough to accomplish something. This is the hardest part since after days without a bowel movement your lower intestines are already full to bursting and adding more liquid to the mix just makes it worse.

I very vividly remember laying on my side in tears in my mother’s bathroom as she pulled my cheeks apart and squirted the Fleet enema in, the whole time saying urgently, “Now don’t let it come out!” I laid that way for about fifteen minutes until I couldn’t stand it and leapt for the toilet. Thankfully, it worked, but it was a few days before I wanted any more than a liquid diet.

My relationship with excrement has pretty much gone downhill from there. Once I had children, my definition of gross changed drastically on the day I found myself sitting in a college classroom certain that I could smell poop. I checked the bottom of my shoes and starting looking around at the people next to me to find the offender. Eventually I noticed the smell got stronger every time my hand came near my face… I turned my hand over and sure enough, there was a line of baby poop smeared up the side right below my pinky finger.

Fast forward a decade and now I have a few more experiences with narcotics under my belt. I’ve learned to avoid my previous pitfall for the most part with proper supplements and diet, but the narcotics I was on following my recent surgery were stronger than anything I’ve had since my original illness; I simply wasn’t prepared. It was five days before I finally broke it to Patrick I hadn’t gone to the bathroom. We were on our way in to my post-op follow-up appointment and I had just thrown up the entire contents of my stomach. The doctor was concerned enough by my admission to call in the advice nurse who specializes in such things; the advice nurse seemed very concerned. I was weak, my pallor was poor, and my stomach wasn’t letting anything else in until I fixed this. The nurse was very concerned and advised us to go the emergency room if this went any longer. Since we were in the area, and already had a nice hospital wheelchair, we went straight to the emergency room from the doctor’s office.

Constipation does not rate high on the triage scale, unfortunately, and after one failed Fleet’s during which I sat on the toilet while the nurse haphazardly stabbed the tip of the bottle around squeezing oil all over my rear end, we waited with no further assistance and no resolution for a couple of hours. Waiting is one my least favorite things, right behind waiting with snakes. So we went home.

My mother was at home watching all of the children, and had earlier purchased a Fleet enema in anticipation of this very moment. As mothers do. We ushered Patrick out of the bedroom and I laid on my side positioned so Mom could reach the sink for warm water while I kept my foot elevated on a pillow. As she pulled my cheeks apart, I raised my head, smiled lovingly at her, and said, “Wow, this is just like old times.” Thank you, Fleet, for bringing mothers and daughters together for generations.

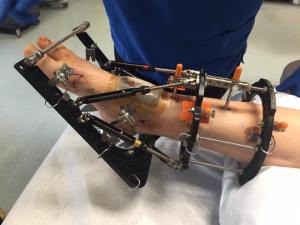

n’t much to see as the frame was wrapped in ace bandages top to bottom, completely shielding the carnage beneath. I asked for a pillow to elevate it and the nurse seemed surprised I could lift my leg without assistance as he tucked a pillow under my ankle. I’ve read many stories from others who’ve had this surgery and they are unable even to bend their knees or move their leg without manually lifting the frame with it, so I immediately felt lucky for my level of mobility.

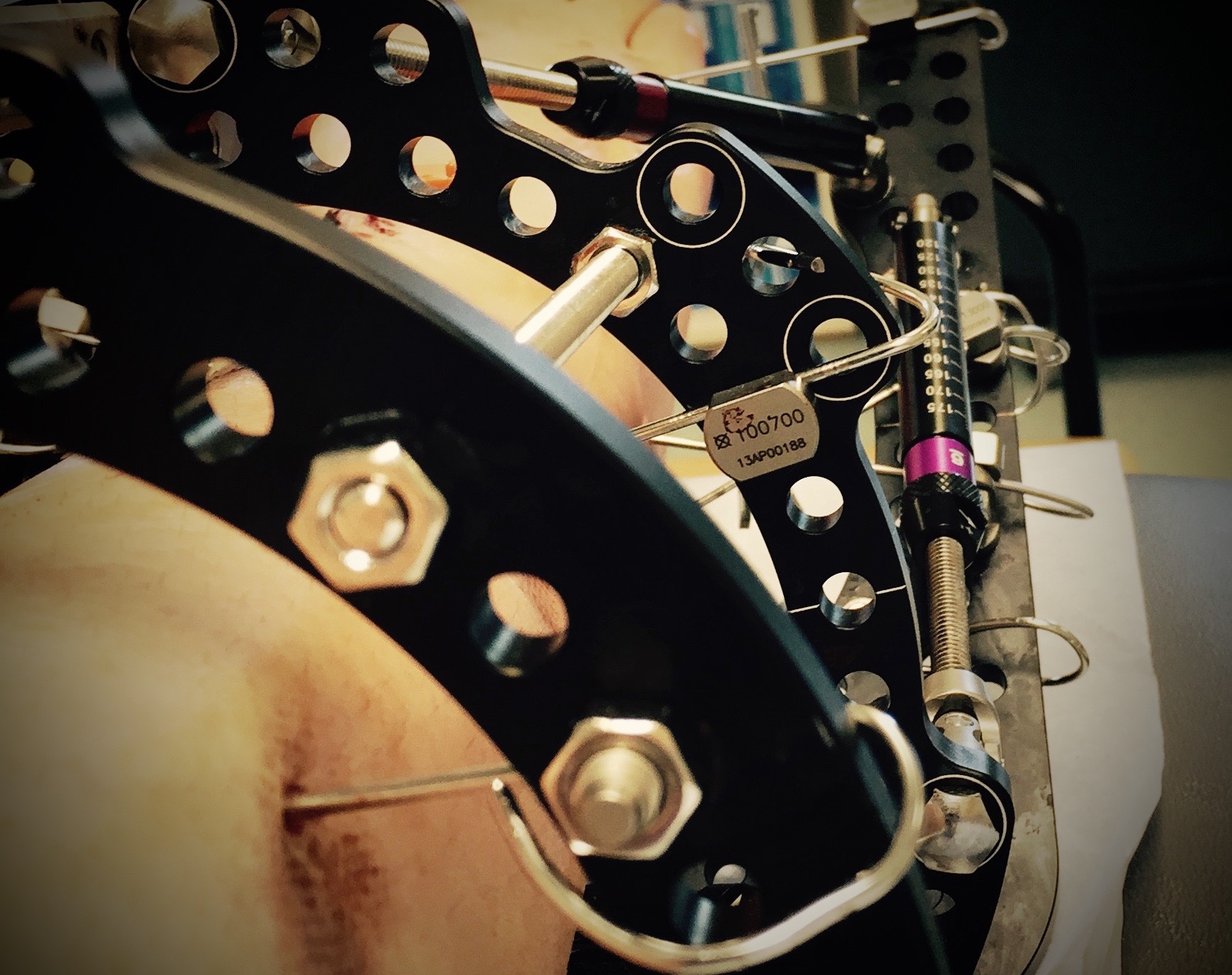

n’t much to see as the frame was wrapped in ace bandages top to bottom, completely shielding the carnage beneath. I asked for a pillow to elevate it and the nurse seemed surprised I could lift my leg without assistance as he tucked a pillow under my ankle. I’ve read many stories from others who’ve had this surgery and they are unable even to bend their knees or move their leg without manually lifting the frame with it, so I immediately felt lucky for my level of mobility. leg holding one side of the frame to the other. Additionally, four metal rods about a half-inch (Patrick says a centimeter, whatever) in diameter were drilled into the front of my tibia. In all, I have 18 holes with metal protruding out of them, or 18 pin sites as they are called in the biz. Another way to look at is 18 entry points for germs to travel straight to my bones. Infection right now is my primary enemy and my first concern is keeping those pin sites clean.

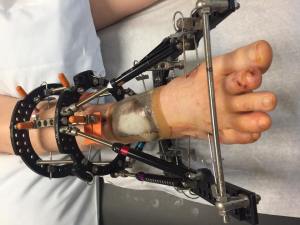

leg holding one side of the frame to the other. Additionally, four metal rods about a half-inch (Patrick says a centimeter, whatever) in diameter were drilled into the front of my tibia. In all, I have 18 holes with metal protruding out of them, or 18 pin sites as they are called in the biz. Another way to look at is 18 entry points for germs to travel straight to my bones. Infection right now is my primary enemy and my first concern is keeping those pin sites clean. sition. In the office during this visit, the surgeon noted that one of my struts had gone slack and the number was 3mm longer than it should have been. She tightened it minimally in the office and directed us to reset it the rest of the way when we got home. That night, Patrick turned the strut, talking to me the whole time so that I didn’t even realize he was doing it. No pain.

sition. In the office during this visit, the surgeon noted that one of my struts had gone slack and the number was 3mm longer than it should have been. She tightened it minimally in the office and directed us to reset it the rest of the way when we got home. That night, Patrick turned the strut, talking to me the whole time so that I didn’t even realize he was doing it. No pain.