Monday, June 15, came EARLY. We had to get up at 3:30 to make the hour drive for check-in at 5:30. Naturally, I hit snooze until 4:15. I packed almost nothing, responding to Patrick’s concerns over this with my certainty that I would be issued a lovely hospital gown and all necessary toiletries would be provided. Besides, I had no one to impress. For a fleeting moment I considered the likelihood that my mother would snap a groggy-eyed photo of me in recovery to post on facebook. As this couldn’t possibly be any worse than the Christmas morning photos in my pajamas with geyser type hair on half my head and my lips so dry they apparently stayed tucked up onto my gums showcasing my chipmunk teeth, I shrugged it off.

I tip-toed into the kids rooms and gave them fierce hugs and kisses that half-woke them from their dreams and said goodbye. In the back of my mind were all the random stories you hear of people going in for a routine surgery and dying on the operating room table because their anesthesiologist was a closet coke addict and forgot to turn on the oxygen. Or similar scenarios. This surgery was not routine or short and was scheduled to last half the day.

On the drive there, Patrick got coffee. For himself. I was not allowed to eat or drink, presumably because if you do die on the operating room table, they want you looking as slender and beautiful as possible. I was silent for most of the drive, but I can never stay introspective for long and soon Patrick had me laughing. Somewhere along that drive it occurred to me that although it would be long and torturous for Patrick and my mother to sit and wait for word of how I fared, I would be asleep that whole time. For me the surgery would be “Oh, I’m feeling groggy,” and then I’d wake up. That lightened my mood quite a bit.

Check-in was fast and as expected I was issued an amazing Vera Wang-esque hospital gown upon admittance. I stubbornly demanded underwear and the nurse gave me a pair of white mesh panties new mothers get after delivery. I secretly loved them. Before Patrick could join me to wait for the surgeon, I went through the necessary scrubbing of the leg, iv inserted, monitors stuck haphazardly across my chest, and – this is the best – a hose blowing warm air was attached to an opening in my gown. My hospital gown filled up with air and they covered me with a blanket pulled directly out of a warming oven. As I crossed my arms and waited for Patrick to be ushered in, I noticed the warm air was filling out my normally frail bosom quite nicely. Patrick noticed too and complimented me on my rack as he entered. Maybe it was the Oxycodon and Valium they had just given me, but it all seemed not so terrifying at that moment. We talked about how much food I intended to eat when I woke up and as each new specialist came in to introduce themselves, I would slide in a comment about preferring to wake up with all my limbs still attached. When my surgeon arrived, I asked her if she’d gotten enough sleep and had all her coffee that morning. She laughed slightly, but I could tell she was already in the zone and focused on getting this shit done right. Her demeanor set me at ease.

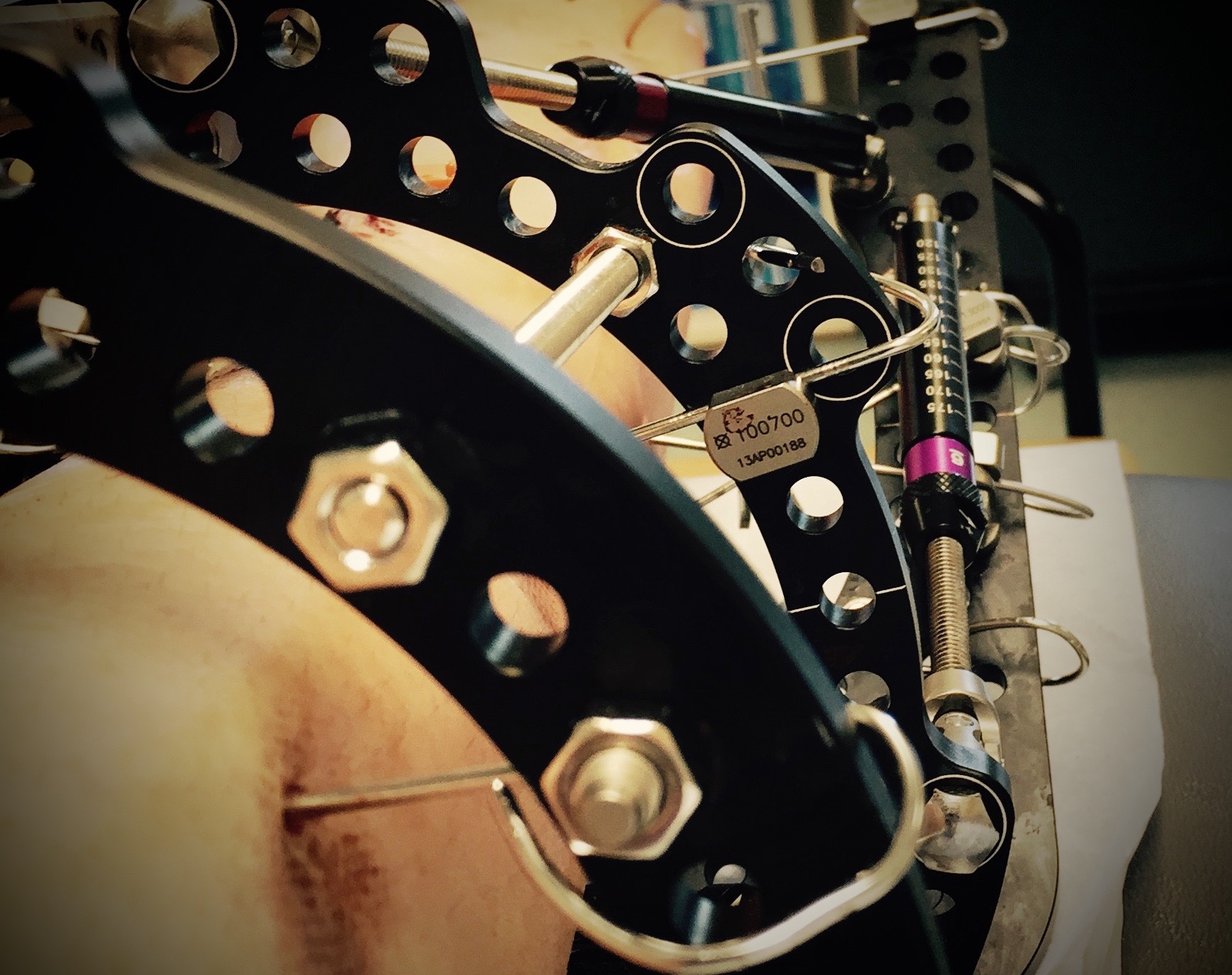

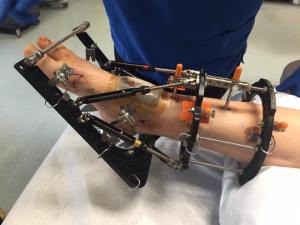

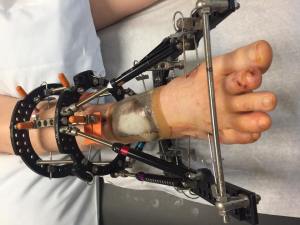

In my surgeon’s own words, the actual ankle surgery, or osteotomy, is a fairly minimally invasive, straightforward procedure. With a small number of short incisions in the front and sides of my ankle, she would be able to fit a wire around the existing bone and essentially saw her way through where there used to be a joint, separating my tibia and fibula from the talus bone. These incisions would then be stitched up and the frame would be affixed using wire that would drill through one side of my limb, through the bone, and come out the other side. These wires would be inserted in my foot at the top just below my toes, in my heel, and in my leg at counter angles to prevent lateral movement of my limb along the length of the wires. The ends of the wires would be wound around bolts along the frame and tightened to create a tension-bearing member capable of withstanding the force required to shift my bones without stretching or bending. External fixation has been around a while, but the Taylor Spatial Frame is a relatively recent invention which utilizes fixation and gradual correction to modify bone. While my surgery is fairly basic and unexciting for a surgeon who specializes in limb deformities, some of the miracles these contraptions can achieve are nothing short of life-altering and awe-inspiring.

My last memory was in the operating room performing a flawless butt-scoot from the gurney to the operating room table. I vaguely remember seeing my surgeon’s face, and then I awoke in recovery. I guess it hurt, I don’t remember it that well as the recovery nurse was quick with the good drugs whenever I started to grimace. I looked at my leg right away, but there was n’t much to see as the frame was wrapped in ace bandages top to bottom, completely shielding the carnage beneath. I asked for a pillow to elevate it and the nurse seemed surprised I could lift my leg without assistance as he tucked a pillow under my ankle. I’ve read many stories from others who’ve had this surgery and they are unable even to bend their knees or move their leg without manually lifting the frame with it, so I immediately felt lucky for my level of mobility.

n’t much to see as the frame was wrapped in ace bandages top to bottom, completely shielding the carnage beneath. I asked for a pillow to elevate it and the nurse seemed surprised I could lift my leg without assistance as he tucked a pillow under my ankle. I’ve read many stories from others who’ve had this surgery and they are unable even to bend their knees or move their leg without manually lifting the frame with it, so I immediately felt lucky for my level of mobility.

It took three hours for a room to open up on the med-surg floor. Once it did, my experience went downhill. My surgeon had prescribed Oxycodon, morphine, and Tylenol. Sadly, this was not helpful and I writhed in agony sobbing until my nurse’s shift ended and she gave bedside passdown to the night nurse. I interrupted them to demand that someone call my doctor, at which point the nurse said they really didn’t like nurses to do that. My new night nurse acquiesced and my doctor not only prescribed much heavier pain medication, but also expressed annoyance that she hadn’t been called sooner. I might have taken the time to look smug if I hadn’t been in so much pain. Eventually the pain abated, but I hardly recall the rest as I was heavily stoned for the remainder of my stay. I vaguely recall pushing a button marked pain whenever I would start to feel anything, and in short order soemone would come in and shoot something into my iv, bringing relief in as little as five minutes. I had to pass a physical therapy test on crutches before they would allow me to leave, and Patrick staying right next to me the whole time for fear I would collapse. I was so stoned you guys.

I was released Wednesday, just as a migraine hit me and forced me to vomit up all of my meds. They gave me this Zofran for nausea which sits under your tongue and claims to dissolve like magic. The reality is that it sits under your tongue and makes you more nauseous as it mixes with your saliva and tastes like glue. It might be the worst invention ever.

All I remember about going home was laying across the back seat as Patrick swung by to pick up his five-year old daughter and explain that for just this once she would need to ride in the front. Her eyes got huge and she immediately rallied at the sacrifice. The next few days are sketchy. I laughed a lot. Patrick worried I was too stoned and starting cutting back my medication. At night he set his alarm for every hour and a half so he could get up and give me more medication, and he tracked every pill and dosage and time in a notebook with a diligence I wish I’d put into my kid’s baby books.

On Friday, I got to see my foot. Seven metal wires ran through my foot and  leg holding one side of the frame to the other. Additionally, four metal rods about a half-inch (Patrick says a centimeter, whatever) in diameter were drilled into the front of my tibia. In all, I have 18 holes with metal protruding out of them, or 18 pin sites as they are called in the biz. Another way to look at is 18 entry points for germs to travel straight to my bones. Infection right now is my primary enemy and my first concern is keeping those pin sites clean.

leg holding one side of the frame to the other. Additionally, four metal rods about a half-inch (Patrick says a centimeter, whatever) in diameter were drilled into the front of my tibia. In all, I have 18 holes with metal protruding out of them, or 18 pin sites as they are called in the biz. Another way to look at is 18 entry points for germs to travel straight to my bones. Infection right now is my primary enemy and my first concern is keeping those pin sites clean.

You can see in the side view photo the adjustable struts connecting the frame along the bottom of my foot to the frame just above my ankle. There are six of these and starting about ten days out of surgery, I will turn each one to a prescribed number to stretch the soft tissues and Achilles tendon at the back of my ankle, widen my joint space to enable movement, and subsequently rotate my entire foot up to a flat po sition. In the office during this visit, the surgeon noted that one of my struts had gone slack and the number was 3mm longer than it should have been. She tightened it minimally in the office and directed us to reset it the rest of the way when we got home. That night, Patrick turned the strut, talking to me the whole time so that I didn’t even realize he was doing it. No pain.

sition. In the office during this visit, the surgeon noted that one of my struts had gone slack and the number was 3mm longer than it should have been. She tightened it minimally in the office and directed us to reset it the rest of the way when we got home. That night, Patrick turned the strut, talking to me the whole time so that I didn’t even realize he was doing it. No pain.

This should be a breeze.